Investigating the Histories and Futures of Water-Based Crises with Nathan Stanfield

This spotlight interview originally appeared on Archinect as part of its Fellow Fellows series.

What led you to accept the Sam Fox Ambassadors Graduate Fellowship?

Faculty. I’m fascinated by the paradox of design as both framework and content, and both catalyst and backdrop to our experiences. As an Ambassadors Fellow, I’ve been lucky to explore multiple points along that spectrum, working with and learning from faculty like Derek Hoeferlin and Wyly Brown in their research. I love how diverse (yet connected) they are and the interests and expertise of other Professors.

Can you share with us your academic journey and interests? How is this carried out through your research and work as an Ambassador?

My work with Derek on the design of his installation through Exhibit Columbus: New Middles, over the first year of the Fellowship, translated into an opportunity with the Divided City Initiative, which has translated into what I’m working on now. I’m learning through projects like Tracing Our Mississippi and my Degree Project to leverage design as an entry point into national conversations on Indigenous sovereignty and environmental stewardship.

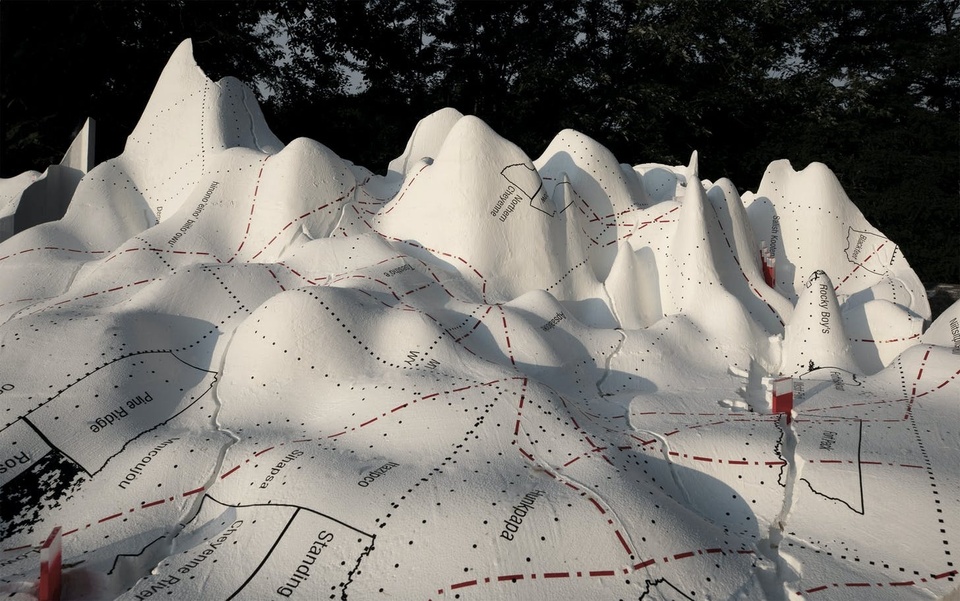

Through my summer 2021 project with the Divided City, I investigated the histories and futures of water-based crises experienced by Native communities throughout the Mississippi River Basin. The first application of my work and research comprised the design, prototyping + stress testing, budgeting + scheduling, and construction of a model of the Mississippi River basin, 800,000 times smaller than reality, which juxtaposes historical Native territories and present-day reservations with systems of power, control, and extraction.

The collaborative project was not exactly the model; rather, it was the nonlinear, iterative, and research-intensive process of making and learning through making. By exaggerating the topography as hydrologists and other scientists graphically do to observe specific phenomena; grossly approximating the subbasin ridgelines, for constructability; CNC milling the main stem rivers not as lines but as ½” wide canyons, a dimension that increases proportionally at reservoirs; exaggerating the levees as ¼” tall, orders of magnitude larger than proper scale; projecting two-dimensional, open-source data and mappings onto a three-dimensional topography through a composite digital and analog process — we aspired not to distort reality but to communicate with both accuracy and legibility the overlooked story of the erasure and manipulation of the watershed’s Native communities and ecology by these relatively recently built, territorial-scale infrastructures.

We abstracted and curated layers of GIS data and open-source information like Native-Land.ca as a counter to the absence of critical engagement with and discussion of these infrastructures and their culpability in issues of environmental injustice. Levees, pipelines, and dams were stitched and scarred across the topography in direct contrast to historically Indigenous territories that were observed to follow topographical and water-based phenomena more closely. Color — specifically white (water), red (power), and black (territory) — built our argument. While the graphic hierarchy and selected layers of information were heavily subjective, the placement and relationships were literal and objective.

The same font style and size were vinyl-cut for cities, historical tribal lands, and present-day Native American reservations to invoke a sense of ambiguity across time, and to draw attention to the connected and often overlapping etymological origins of these places. These decisions, paradoxes, and ambiguities meant to reinforce this impression of the watershed’s increasingly synthetic construction, and to question our quiet acceptance of this distorted reality.

What work are you most proud of from your time at the Sam Fox School?

I’m proud of all that I’ve learned from the people I’ve met through my time at Sam Fox. My Divided City project framework, which focused on three distinct regions — the Twin Cities, St. Louis, and New Orleans — illustrates this idea. I understand my ongoing education to stitch between these three various geographies across this massive Mississippi River Basin scale.

Twin Cities. Drawing from internet rabbit holes, experiences and education in demonstrations, and conversations with individuals who are going North to fight these issues with their bodies and voices, I believe that the present and future of colonial assault on Sovereignty lies in protests, lawsuits, and governmental (in)action against pipeline construction across Native land. The ongoing conflict of the Enbridge Line 3 tar sands pipeline “renovation” (in which a new pipeline is laid alongside an existing one that is left as is) across sacred Anishinaabe rice lakes encapsulates the present and future destruction of Native landscape and breaking of treaties. While these issues of infrastructural neglect and water supply contamination are by no means unique to the greater Twin Cities region, they are particularly evident and present here.

St. Louis. The greater St. Louis area is exceptional in its simultaneous preservation and erasure of Indigenous history, a paradox that emerges from the story of the Mississippian mounds. Cahokia provides an instance of some optimism, juxtaposed by surrounding industry, landfill, and Superfund site. Jesse Vogler, Matthew Fluharty and team’s Charting the American Bottom was instrumental for me in beginning to understand this network of stories. Erasure, meanwhile, is difficult to document because the finding is absence. Though Sugarloaf Mound, under guidance of the Osage Nation, serves as the last known Mississippian mound West of the Mississippi, the destroyed Big Mound and countless others suggest a more cynical narrative. Like in the Twin Cities, this narrative of historical erasure resonates across the country.

New Orleans. As we were putting together a public program in Fall 2021 for Tracing Our Mississippi, collaborating artist Monique Verdin helped me to maintain awareness of the immediacy of our design conversations in the wake of Ida. The urgent reality of flooding and industry-induced climate degradation is clear. The Houma people have been among the first official climate refugees in the United States, and while sea levels continue to rise, heavy industry and resource extraction in the Gulf continue uninterrupted. While the bigger picture reconfiguration and unbuilding of territorial infrastructure remains vitally important, the immediate needs of those most affected by human-induced climate disasters call for resources and work that are desperately needed, and now.

This particular graduate fellowship includes a stipend to further your research. How have you utilized this portion of the fellowship?

Despite limitations on travel during the pandemic, I had the chance to attend Exhibit Columbus: New Middles in person for the installation and exhibition. I am in awe of the creativity of the individual installations, and the overall aspirations of the curators and EC team. The Columbus community was so receptive to the conversations and supportive of the designers — for me, it was an exciting introduction to what architectural research and exhibition work can be.

This past Fall 2021, as part of professor John Hoal’s (Re)Thinking Africatown Graduate Architecture Options studio, I was again able to travel, this time to Africatown in Mobile, Alabama. The trip confronted us with how racism plays out insidiously through the industries that surround and choke both the Delta and Africatown. The trip was a bank of knowledge. It served as a reminder to me, as a designer, all that can only be understood, felt, from physically being at a site and speaking directly with stakeholders and community members over the course of a design exercise.

The past two years have challenged architecture pedagogy for better and for worse. How do you see the future of academia changing? How do you hope it continues to be challenged?

While the process of change is awkward and uncomfortable, I’ve felt a growing culture of empathy in architecture pedagogy. It’s like something as intense as the colliding of the George Floyd protests, global pandemic, and mounting environmental degradation (there are many more to name here) serves as the catalyst in waking us up, again and again. Architecture plays a supportive and culpable role in that process. We need constant reminders to appreciate the beautiful things in our lives and to remind us of everything that is broken.

How has the fellowship advanced or become a platform for your academic and professional career?

My research with Derek and the Divided City has continued into my second and final year of the Ambassadors Fellowship. In a public program in Columbus in October 2021, we projected stories, text, and images from individuals across the Watershed onto the six model subbasins. The idea collapsed territorial concepts into an ephemeral audio-visual experience that communicated this idea of a diverse and complex Watershed Community.

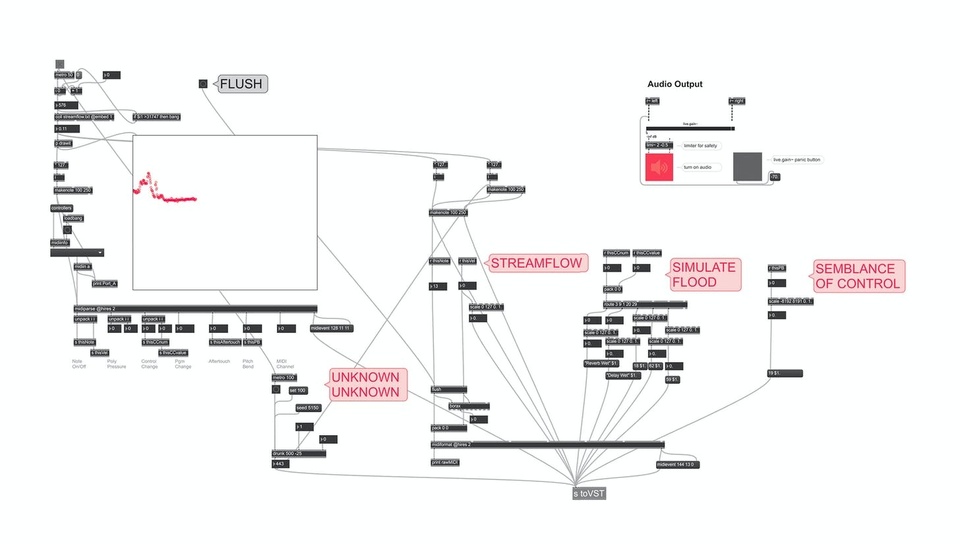

I am very interested in the senses — literally, what we touch, see, hear, taste, and smell — as the fundamental toolkit for designers. Through the flexibility of my program, I’ve had the opportunity to pursue coursework in Hydrology, Construction Management, and Electronic Music, parallel to my architecture studios and research positions. It is my belief and experience that researchers, scientists, and artists are increasingly receptive to cross-pollination across, I would argue, fundamentally siloed departments.

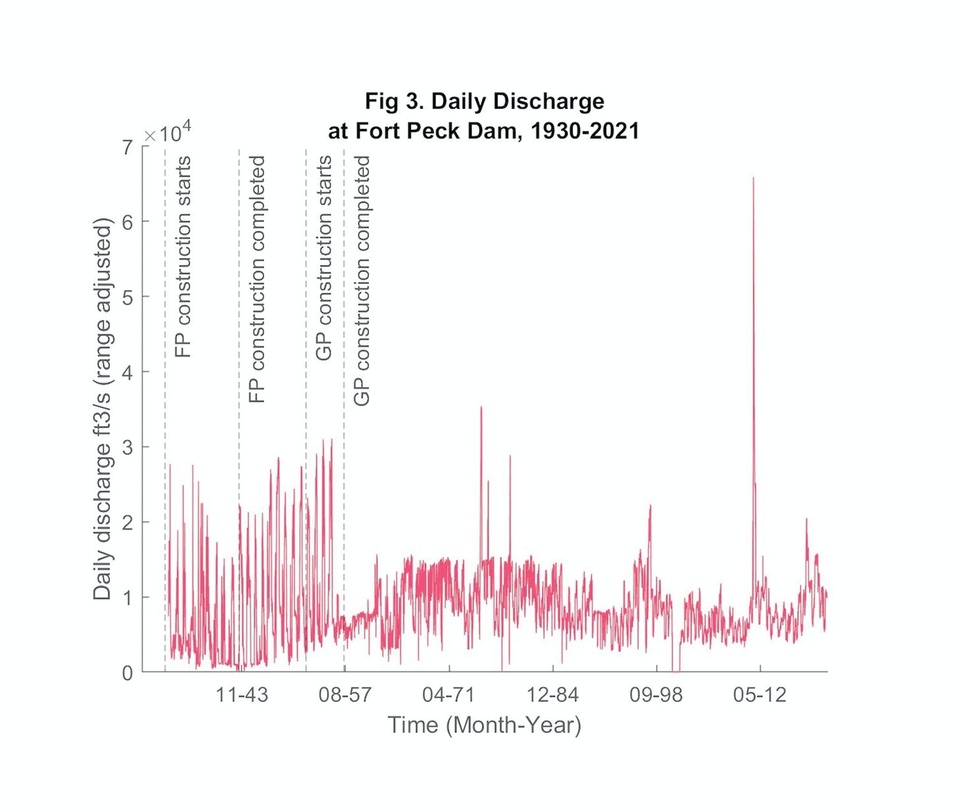

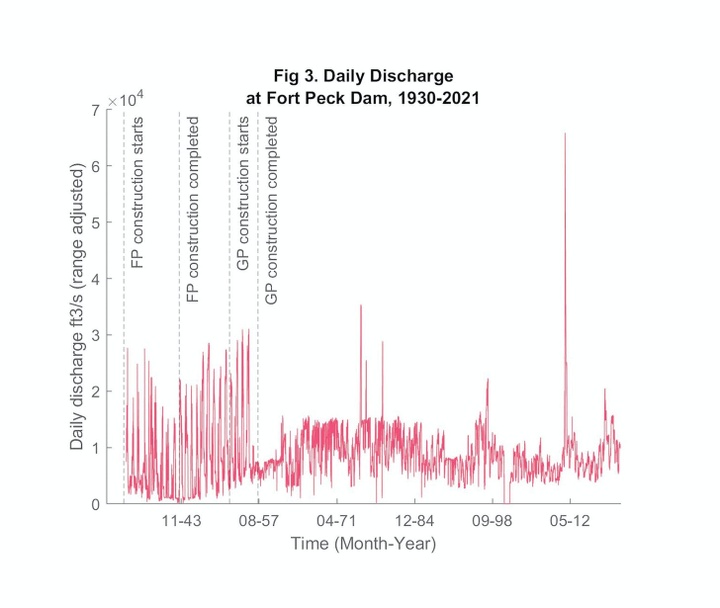

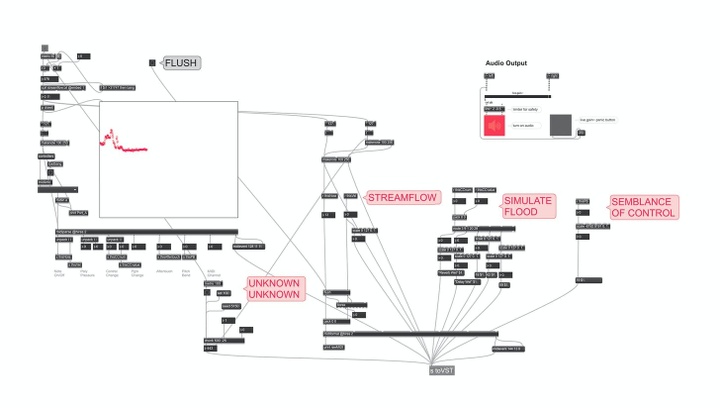

Computation and open-source culture can be conduits for this academic collectivism. Streamflow data at dam sites tell a story of ecological harm that can be translated and understood, by a larger audience, sonically (keep an eye/ear/hand out for Laptop Music’s upcoming installation at the Kemper Art Museum). The relatively simple concept of an overtone flute can be scaled up, if proportions are right, to the same architecture that facilitates stack ventilation as a passive energy strategy. Literally, data are music and buildings are instruments.

Architects communicate through both the technical realization of space and its perception: this duality is a responsibility and opportunity. While Tracing Our Mississippi examined the effects of infrastructural interventions on Native land and water, my Degree Project investigates the history and future of this material extraction in the St. Louis area and speculates the role of architecture in its disarmament.

The project aspires towards speculative practicality. My site in the American Bottom, a large floodplain East of St. Louis and the Mississippi River, draws from my previous research to call out a narrative of exploitation and work against it.

The project supposes Milam landfill’s connection to Native history through the adjacent Cahokia Mounds UNESCO World Heritage Site, and to the future, through pipelines. The waste company that manages (and is expanding) the landfill has installed infrastructure below that uses the trash as energy for these pipeline systems. I am exploring promising precedents in land remediation, long-term architectural phasing, and re-imagined energy conversion that work counter to the damage continually inflicted by the presently inevitable endpoint of material consumption.

The project is current and ongoing. Ultimately, through this process of making and learning through making, I hope to better embed my experience and interests in multisensory perception within my architectural practice.

Any advice for future fellows?

Apply! You’ll be surprised by what you’ll learn about yourself, and your world, by simply putting your ideas and questions into an application. And once you start a program, keep an open mind to change, and what that experience teaches you. I find it continuously impossible to predict what I’m going to learn. Fellowships are a special environment where this kind of nonlinear, exploratory process is not only accepted but encouraged.