Exploring Methods of Resiliency in Society, Ecology, and Design with Kevin Mojica, Sam Fox Ambassadors Graduate Fellow at Washington University in St. Louis

This spotlight interview originally appeared on Archinect as part of its Fellow Fellows series.

What led you to accept the Sam Fox Ambassadors Graduate Fellowship?

Transitioning into graduate school came at an extreme time of uncertainty, in 2020, during the beginning stages of the COVID pandemic. Everything froze, job offers fell through, so I returned home to complete my undergraduate studies remotely. Before starting at Washington University in St. Louis, I attended the University of Florida from 2016 to 2020. I received a Bachelor of Design degree with a major in Architecture and a Bachelor of Science degree in Sustainability in the Built Environment. Both undergraduate degrees simultaneously influenced each other, leading to a symbiotic relationship between the built and natural environment.

The design pedagogy at the University of Florida was much more abstracted. It relied on design fundamentals towards human intuition — unfamiliar to the digital-heavy, emerging pedagogies elsewhere. However, by being located in Central Florida, our studio projects often incorporated natural landscapes and rested on precedents from architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, William Morgan, Paul Rudolph, and Richard Meier. The undergraduate sustainability studies were much more pragmatic and eventually led me to a capstone project, where I focused on refurbishing shipping containers into affordable housing. Using energy simulations and LCA (life-cycle assessment) digital tools, I assessed its viability on its various construction materials and method possibilities. Part of me applied to graduate programs out of curiosity, having no preconceived notions of true intentions on an architectural focus — only interests across the spectrum. Higher education always felt like a far reach for someone as a first-generation Mexican-American from immigrant parents and an impoverished background. Yet it became the reason I ultimately decided to continue these academic endeavors and find a purpose in the discipline of design and architecture — a belief towards the betterment of societal well-being, from the lens of someone who has experienced the adversity of injustice, the everyday human.

Before accepting the Sam Fox Ambassadors Graduate Fellowship, I was approached by faculty who shared with me their various architectural perspectives and backgrounds. Professional and academic work ranged from social housing to urban design, which I was immediately attracted to being someone who didn’t quite grasp the various niches of architecture. Having spent most of my life in Southern Florida, I realized the severity of climate change and its impact on the social and ecological well-being of communities. This ultimately led to my obsession with designing towards resiliency, on which I unknowingly based my later undergraduate studies on with respect to Florida’s landscape. Everything soon coalesced into a series of explorations on the topics of resiliency in society, ecology, and design.

In accepting this ambassadorship/fellowship, I undertook the role of representing the Sam Fox School of Design and its values to its highest degree and leading by example in both the school and city. By engaging in multi-disciplinary courses and the local community, I developed my thesis project around researching the coexistence between urbanity and nature and the recent challenges we have endured from climate change and the pandemic.

Can you share with us your academic journey and interests? How is this carried out through your research and work as an Ambassador?

To understand my interest in design and architecture, I feel it is important to share my background as a first-generation Mexican-American. Only then can I truly express the intimacy and passion I have nurtured throughout my studies. Having been raised in rural Mexico for a quarter of my life, it wasn’t until recently that I became aware of the role vernacularism played in impoverished communities. At the time, it all felt ordinary. There was never a moment when my younger self made sense of the deficiency or embraced its simplicity. There weren’t any HVAC or MEP systems. The traditional village, or pueblo, was full of homes mainly constructed of adobe brick, held together by earth mortar extracted from nearby local grounds. In our home, once occupied by ten family members, built by my grandfather — a farmer, there are two bedrooms, a kitchen, and a large living space, all open to the southern exposure of the sun and mercy of the central-valley Mexican climate.

The size and organization of the spaces influence a social interaction among the household members and cultivate a Mexican culture familiar in the Latin Americas. As bare as this description may seem, we as a family were content with the number of resources we had, grateful for a shelter above our head and our casita’s flexibility. However, later on, as we moved to the United States, it was the complete opposite. “Ordinary” wasn’t a familiar feeling, and there was a clear distinction between our living conditions compared to neighboring luxuries.

Growing up in poorer homes affected us socially throughout our advancement in education and socialization, understanding we aren’t as privileged as other groups/families regarding amenities, space, and security. From single-bedroom apartments to prefabricated mobile homes — or trailers as we know them — it suddenly became obvious there exists a disproportionate convention of building materials and systems for low-cost construction in relation to their surrounding landscape and climate. The impacts of climate change are not unfamiliar to the region of South Florida. Having been battered continuously by intensifying sea-level rise and hurricanes, the inclement threats barely spare our home with minimal flooding and damages throughout the hurricane season — but not everyone is as lucky.

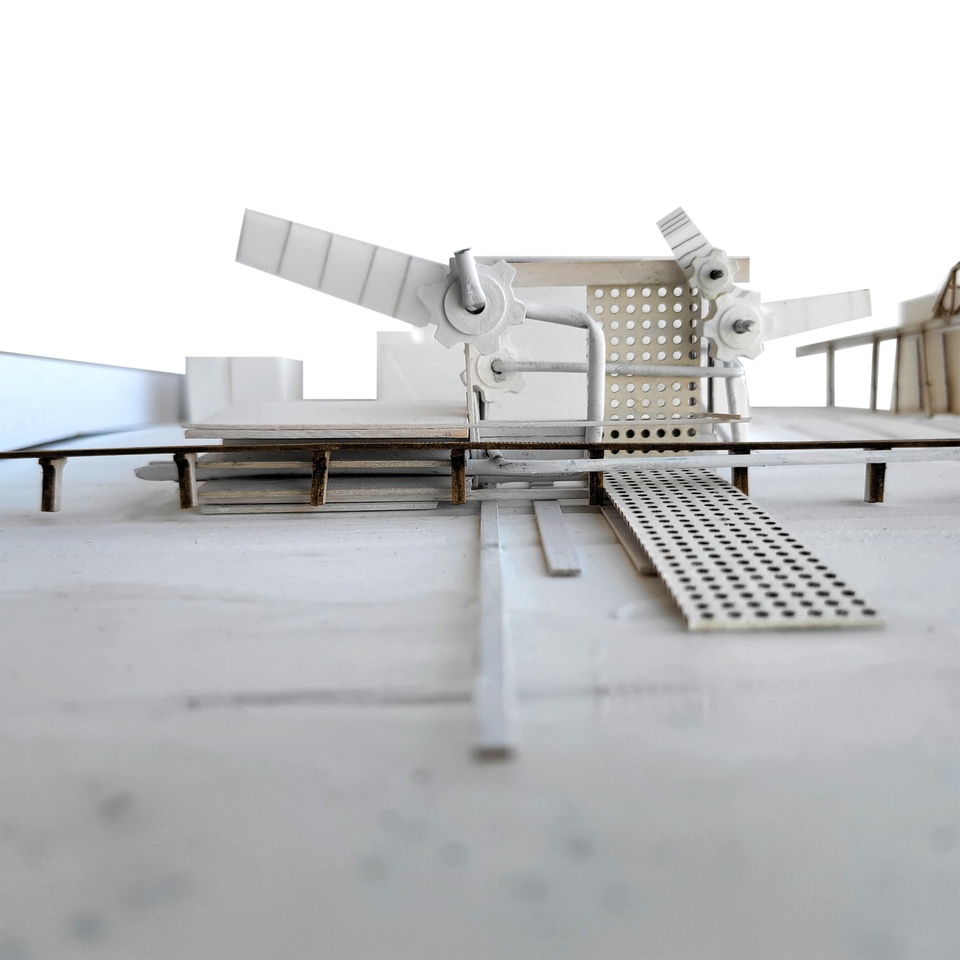

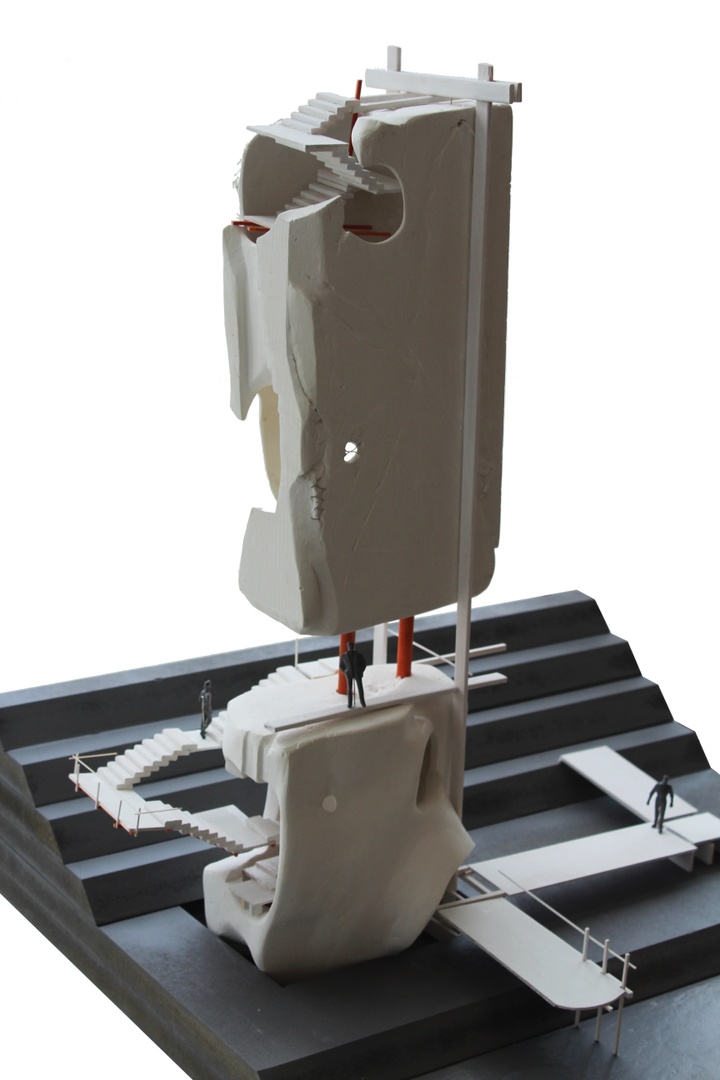

At the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, I’ve worked in studios and seminars focused on climate-related issues and their design responses. Some courses included “Dynamic Materialism and Urbanism” led by professor Sung Ho Kim and “Pre-Cast Concrete Enclosures” led by Professor Pablo Moyano. Each of these courses dealt with different environments and scales but focused on the role of materials and system performance during unsuitable climate conditions. The seminar “Pre-Cast Concrete Enclosures,” in Spring of 2021, was a collaborative project on the design and fabrication of a 5’ x 10’ GFRC (glass fiber reinforced concrete) wall panel, with the partnership of Gates PreCast Construction and the sponsorship of PreCast/Prestressed Concrete Institute. The project dealt with the functionality of prefabricated panels concerning water runoff/collection, resource efficiency, thermal comfort, and resiliency to extreme weather conditions. For my Master of Architecture thesis/degree project, I have focused on the resiliency of the St. Louis urban riverfront and its future as a river city through an urban/ecological intervention. This final project is a culmination of previous undergraduate research and my background degree in Sustainability in the Built Environment. I have been exploring LCA (life-cycle assessment) of materials and systems, water use and adaptation, energy performance, passive design strategies, and social and climate resiliency appropriate to the neglected region.

What work are you most proud of from your time at the Sam Fox School?

Distant from the research in resiliency, I had the privilege to work with the Director of Architecture at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, Heather Woofter, and Professor of Practice, Sung Ho Kim, on a community project. The position was made possible through a Research Assistantship in Fall 2021 and dealt with the design and fabrication of stage design for a local arts center called COCA (Center for the Creative Arts) in St. Louis, Missouri. My colleague, Yulia Morina, and I were tasked with analyzing a theater’s play and its conceptualization of physical construction using digital fabrication and hand-modeling techniques under the coordination of project manager Jae Bum Byun.

Our role as designers was put to the test in an actual commissioned project and our social skills and understanding of St. Louis. We frequently had to engage with professionals from COCA and community members. To offer some context, the play itself was a modernized version of the film “Alice in Wonderland” for a play consisting of students from grades 6–12 in the creative arts. Together with Axi:Ome (Heather and Sung Ho’s office) and research assistants, we designed and fabricated the primary stage, set props, and scenes for different parts of the theater performance. Items included a large table, bed, royal throne, forest scene, proscenium, and sculptural figures.

The methods to design and fabricate started from hand sketching to digital modeling and eventually to my coordination of CNC milling half of the project items. The pride that stemmed from this project didn’t come from our rigorous work but from seeing theater members use our items. The excitement from the theater’s performers and students was reassuring of our hard work and attention to detail. Our university is in St. Louis, a troubled city by its social injustices. It was comforting to see the brighter side of joy we could be a part of — in a diverse and optimistic community of creatives.

This particular graduate fellowship includes a stipend to further your research. How have you utilized this portion of the fellowship?

The Sam Fox Ambassadors Graduate Fellowship provides a stipend to further our research through travel, crafting materials, and other forms of learning. One way I utilized the stipend was by purchasing books on interesting topics of design and urbanism. Some books include: Soft City by David Sim, The Barefoot Architect by Johan Van Lengen, Designing for the Modern City by Eric Mumford, and Can a City be Sustainable? (State of the World) by the Worldwatch Institute. These texts, along with many others, transformed my understanding of urbanity and the importance of the human scale. In other words, we as designers can be compulsive to the appearance of our creations and fail to benefit the very people who may use them. There is an inherently social and ecological responsibility. Aside from books, another way I utilized the stipend was by short travel, given the constraints of the pandemic. My research up to this point has been inspired by the existence of the Mississippi Riverfront and the role it plays for St. Louis. To comprehend the complexity of the Mississippi River, I have visited various cities along its northern tributaries, including Chicago, and even at one point canoed down its mighty flow in St. Louis.

The past two years have challenged architecture pedagogy for better and for worse. How do you see the future of academia changing? How do you hope it continues to be challenged?

The impact the pandemic has had on academia varied tremendously throughout architecture schools. Some schools transitioned 100% online and transformed their physical collaborative studio spaces for virtual pin-up spaces; others, like Washington University in St. Louis, hybridized the studio environment and allowed for regulated in-person studio work and instruction — which I was grateful for. However, the two-year absence of a consistent in-studio learning environment complicated the pedagogy of design by revealing the extents of 3D digital modeling, such as Rhino, Revit, SketchUp, etc. It is incredible to have witnessed and been a part of the digital transition from tangible drawings and models to the representation of images via a shared computer screen. Yet there was and still is a significant concern that future generations lose the tactility in design. In solely relying on the transformation of concepts to buildings or spaces via 3D modeling software, you expose the realities of the egotistical nature of the designer — foreign objects.

Understanding architecture and design through sensory experiences allow for an empathetic approach to its users and reveals the intangible narrative of the project. It can’t just be an object — floating around the cartesian void of your computer. In the practice of architecture, we must acknowledge our surrounding context — its people, nature, cultures, history, buildings, transportation, and the soft and hard infrastructure of the city, to name a few.

There is an inherently social, cultural, economic, and environmental responsibility to the role of a designer in the architecture discipline; the impact an architectural intervention can cause on the existing urban fabric is immeasurable. As much as I would like to consider architecture as merely art, there are consequences when ego or ignorance overtakes design and leads to inappropriate interventions. The individual designer(s) has the privilege of imagining a construction to benefit its clients or communities, nature especially; opposingly, when it is created for the sake of the glorious form, we fall into the exploitation of resources and society.

Returning to the question of change the past two years have caused in design pedagogy, I believe it has revealed its vulnerability to the computer. As someone who enjoys digital design and fabrication, it may be more constructive to use these tools as methods of quantitative analyses, rapid prototyping, or iterative processes. Optimizing projects through aspects like energy and climate performance are nearly impossible without computer-aided design and should be continued in pedagogy towards a more sustainable expectation. But as we recover from the severity of the pandemic, I hope to see academia push for the recovery of the in-person studio environments and rigorous craft by hand — the intimacy of the designer, at the scale of the everyday.

How has the fellowship advanced or become a platform for your academic and professional career?

The Sam Fox Ambassadors Graduate Fellowship has given me a platform to share my past and current research with peers and professionals directly through discourse and indirectly through social media outreach. In addition, the title as a fellow has allowed for more exposure through platforms like LinkedIn and led to a recent fellowship with global design firm Gensler in the Summer of 2021. The Gensler Summer Fellowship embraced research-driven design on climate change, social injustice, and the future of cities. The Gensler Fellowship was composed of a cohort of 40 students and young professionals worldwide, and I was honored to be the only student and representative from Washington University in St. Louis.

Most recently, I was honored to be included as one of 15 nominees for a prestigious exhibition and competition at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, called the Frederick Widmann Student Exhibition, which recognizes the top students in the graduate architecture program. Through this ongoing competition and exhibition, I have shared my collection of personal and academic work throughout my time at the Sam Fox School. Aside from personal gain, I have had the privilege of speaking with prospective graduate students for the Sam Fox School and sharing my experiences in the M.Arch program. These brief encounters have led to conversations on the interests and skillsets prospective students may bring to the university. In it, I direct students to faculty or colleagues whose research aligns with theirs — ensuring a continuation of education.

Any advice for future fellows?

As a Sam Fox Ambassadors Fellow, the role has allowed me to expand my focus on the subjects I find most compelling to my growth as a designer and architect. It is fundamentally essential to allow yourself the opportunity for new research outside of your preconceived specialties, especially in the ever-changing field of the design and construction industry. In a discipline of many trades, understanding the different components of urban environments allows for a deeper understanding of the complexity of the intervention of architecture. Eventually, these findings will merge in your specific fields of interest and strengthen their relevance to their importance in the discipline. Trust your intuition and allow your socio-cultural experience to pave the direction of your research’s intents. Whether it be quantitative or qualitative studies, it returns to the scale of the everyday person. I firmly believe there is a necessary obsession required to convey your research. Deriving it from a deeper emotion, imagination, nostalgia, or what be it, can only strengthen its impact on its empathy towards human-centered design. Your significance to the discipline has been recognized, and your role as a future designer and leader.

Any advice for future fellows?

As a Sam Fox Ambassadors Fellow, the role has allowed me to expand my focus on the subjects I find most compelling to my growth as a designer and architect. It is fundamentally essential to allow yourself the opportunity for new research outside of your preconceived specialties, especially in the ever-changing field of the design and construction industry. In a discipline of many trades, understanding the different components of urban environments allows for a deeper understanding of the complexity of the intervention of architecture. Eventually, these findings will merge in your specific fields of interest and strengthen their relevance to their importance in the discipline. Trust your intuition and allow your socio-cultural experience to pave the direction of your research’s intents. Whether it be quantitative or qualitative studies, it returns to the scale of the everyday person. I firmly believe there is a necessary obsession required to convey your research. Deriving it from a deeper emotion, imagination, nostalgia, or what be it, can only strengthen its impact on its empathy towards human-centered design. Your significance to the discipline has been recognized, and your role as a future designer and leader.